Lean Construction 101

- Principle: Continuous Improvement

- Strategies: Never Settle; Collaborate

- Principle: Integrated Decision-making

- Strategy: Integrated Project Delivery

- Principle: Ongoing Decision-making

- Strategies: Pull-flow; Decentralized Decision-making

Lean Construction is an approach to project management that has been gaining traction in the construction industry, with a focus on efficiency and productivity. It is based on Lean Manufacturing principles, which have been used for decades by companies such as Toyota, Dell and Amazon.

The goal of Lean Construction is to reduce waste and maximize value during the construction process. This involves looking at every aspect of a project – from design to execution – and finding ways to streamline them or remove anything unnecessary or wasteful.

One of the primary challenges of understanding Lean Construction is that the overall goal and guiding objective, maximizing efficiency, is so simple and so obviously desirable. Efficiency is always one of the goals of any construction project, so what makes Lean Construction any different? How do you apply such a vague goal to a specific project with all of its unique circumstances and constraints?

Distinguishing Lean Construction from other approaches requires understanding the guiding principles and strategies that help managers aim at maximizing efficiency, thereby bridging the gap between abstract theory and concrete methods. Indeed, it’s best not to think of Lean Construction as a totally different way of doing construction but as a collection of strategies for maximizing efficiency that work better than conventional methods.

Principle: Continuous Improvement

Continuous improvement is a way of doing construction that comes from Lean Manufacturing principles. It’s the view that no project or method is perfect, and construction managers should always look for ways to make things better.

This means looking at every part of the construction process, from design to execution, and finding ways to make it more efficient by removing anything unnecessary or wasteful.

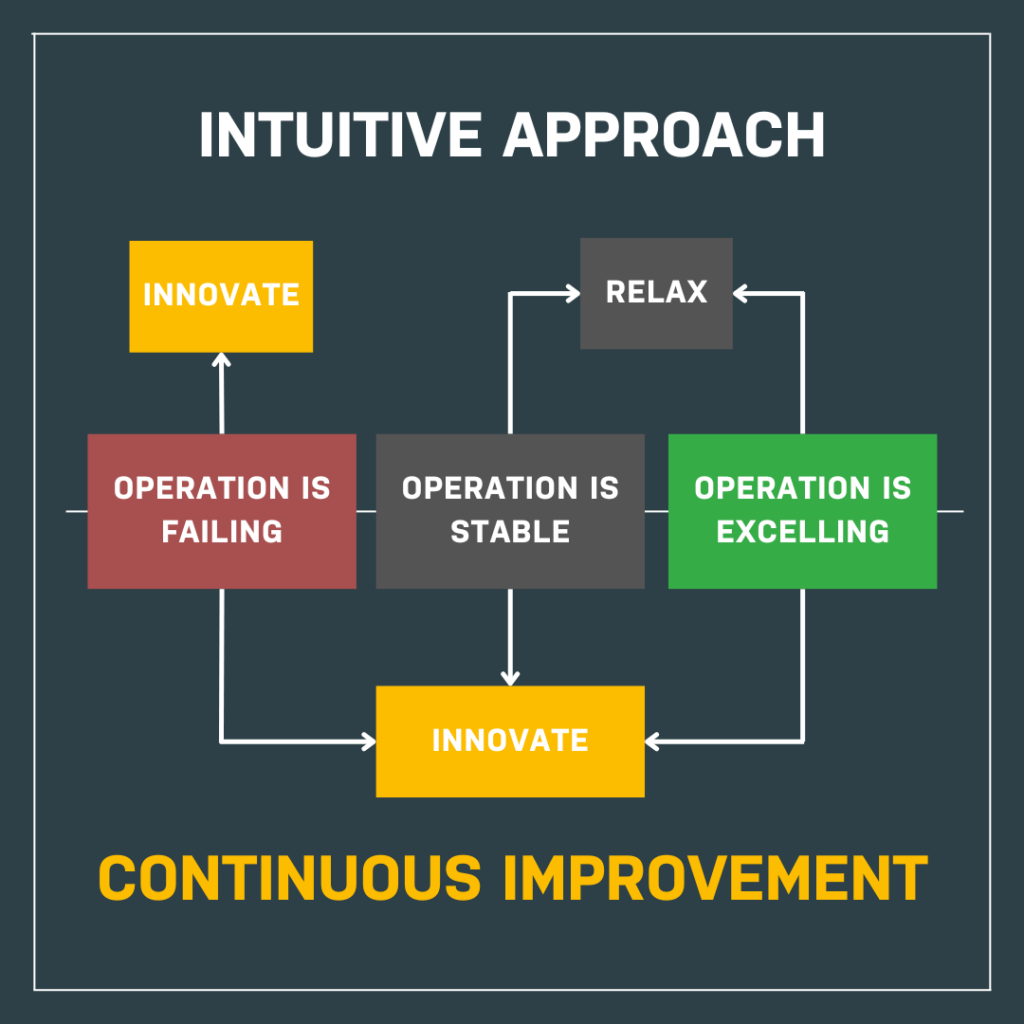

Conventional approaches to construction or any other kind of project tend to think of innovation as a remedy for poor performance. You only consider ways to improve a process or method when that process or method stops yielding desirable results, like a machine which is neglected when functional and repaired or replaced when it breaks down or is no longer needed.

This is a restorative approach to innovation, where it is a tool used to put things back together and return to the previous status quo results. When things are running smoothly, and results are satisfactory, you can relax innovation and focus on other things. Things are “good enough.”

In contrast, Continuous Improvement means never settling for “good enough.”

- When everything is breaking down, and your operation is suffering from severe dysfunction: innovate and improve.

- When your operation is running smoothly, and you’re turning a comfortable profit: keep innovating and improving.

- When your operation is excelling and out-competing every one of your competitors: keep innovating and improving.

Strategy: Never settle for good enough

As a project manager, embracing the principle of continuous improvement means paying close attention to your own feeling and thinking: reminding yourself that there is always room for improvement, no matter how well things are working right now. Never allow yourself to be closed off to new suggestions, and always try to keep an eye out for improvement opportunities.

Strategy: Collaborative decision-making

It also means accepting that you don’t have perfect judgement and perception in recognizing opportunities for improvement; accepting that good ideas can come from other members of the team as well. Managers who do not consider the input of everyone involved are sacrificing a huge amount of cognitive resources that could be added to the team’s overall decision-making capacity. Even if you have the most experience and the greatest insight, why not add to it?

However, it’s not good enough for you to be receptive to ideas and feedback from all members of your team. Your position as the manager and decision-maker means that the rest of your team is not likely to give you their input unless they think it’s crucially important.

Resigning yourself to passively accepting what ideas are brought to you by your team means missing out on the vast majority of what they might be able to contribute. Ask them what they think, and encourage them to develop new strategies and methods.

Principle: Ongoing and Integrated Decision-making

In a conventional approach to project delivery, decisions are made by a small team of planners (eg. the owner, the architect, the project manager) in the abstract, and then that plan is carried out in the real world by workers, technicians, and site managers.

The builders are just there to receive and follow instructions; no one is interested in the insights they might be able to provide.

Again, this is an intuitive way to carry out a project; after all, that’s what the designers and architects and managers are there to do, to plan, right? The trouble with this approach is twofold: planners often lack practical experience, and planners can’t plan for everything.

Integrated decision-making

Architects, engineers, and project managers are typically very smart people, but there’s no substitute for hands-on, practical experience.

If a small team of decision-makers develops a plan with unrealistic budgeting, forecasting, or other unrecognized flaws that make the plan unfeasible, they might not find out until weeks later when an on-site manager has to explain it to them over the phone. At this point, the project is stalled until the decision-makers can adjust the plan, issue new instructions, and make any required logistical arrangements.

Strategy: Integrated Project Delivery

Alternatively, if the planning phase had included the builders and their practical experience, these flaws could have been spotted early and corrected before being committed to. “Integrated Project Delivery” is the standard term for an approach which involves all perspectives and parties in the decision-making process; the builders, designers, architects, owners, customers, and managers. The planning phase isn’t complete until everyone has had a chance to provide input.

Ongoing Decision-making

It’s simply not possible to predict and account for every challenge or complication your project will face along the way. The construction process is dynamic and ever-changing, so the plan needs to be constantly updated as new challenges arise.

The construction manager has to maintain a constant information loop between all of the different perspectives to ensure that everyone is still on the same page. This doesn’t just mean making sure everyone knows what’s happening right now; it also means staying ahead of the curve and ensuring that everyone is aligned with the overall construction goals.

Strategy: Pull-flow procurement

In any project which transforms input materials into a finished product, the movement of materials through the process can be conceptualized as a flow. This abstraction is obvious in manufacturing, where Lean Project Management principles were first developed, but it’s also relevant to construction.

In a construction project, basic materials (eg. wood, steel, concrete; ie. “inputs”) are transformed into a finished structure (“output”).

In a conventional construction approach, the planners forecast the amount of each type of material they’ll need ahead of time and then procure all or a portion of that total at the beginning of the project.

This is sometimes called “push” flow, as the material is first gathered or created and then pushed to the final product. The problem with push-flow procurement is that over-estimating or under-estimating the amount of material you’ll need is costly and wasteful. Over-estimating wastes money and material; whereas under-estimating wastes time if builders have to wait on more supplies.

Lean Construction instead accepts that the precise amounts of material that will be needed are difficult to predict ahead of time and instead procures only a small amount of each material at the beginning to get started. From there, material reserves are closely monitored, and small refills are procured as necessary. If done well, by the end of the project, the total amount of material procured will be almost exactly as much as was needed.

Strategy: Decentralized decision-making

Another way to maximize speed and efficiency is to spread out the burden of decision-making, empowering site managers and other lower-level members to make certain decisions on their own; without consulting or seeking permission from the planning team.

The specific types of decisions these managers should be allowed to make will depend entirely upon the kind of background and experience they have and the nature of the project. However, if you can delegate the smaller, less-impactful decisions to those on the ground actually building the project, then you cut these smaller matters out of the communication loop between builders and planners, saving a huge amount of time.

Lean Construction with Bilt

At Bilt, we understand that construction projects can quickly become bogged down by poor communication and inefficient processes. That’s why our construction management services are built on a foundation of Lean Construction principles. We know how to optimize construction sites for maximum efficiency and productivity, so you can get your project completed faster and on budget.

Contact us today to learn more about Lean Construction with Bilt and how we can help you get your construction project done quickly and efficiently.